💍 A True Story of Len and Betty

They met in Flint, Michigan, in 1963—not a fairy tale, not a movie, just a bar filled with cigarette haze and two people trying to start over. She was recently divorced and out with a friend. He’d just clocked out from the Flint Police Department, a 101st Airborne paratrooper still carrying the discipline of service and the restlessness that comes after it. He asked her to dance. She said yes. A small, ordinary yes that changed everything.

Because Len was still finalizing his previous marriage when he proposed to Betty, they drove to Angola, Indiana—one of the few Midwestern towns where you could marry before a divorce was legally finalized. Angola was basically Vegas for people with Midwestern guilt: a courthouse, a signature, and you were hitched. They married there on December 8, 1963, then renewed their vows the following April once the paperwork caught up in Michigan.

💼 Work, Duty, and the Long Game

Len was the kind of man who worked his way through life with clean hands that somehow still looked like they’d been through hell. He graduated from Copemish High School, ran track, enlisted with the 101st Airborne Division, served overseas in Germany, joined the Flint Police, and eventually worked his way into management at General Motors, where he became a Foreman.

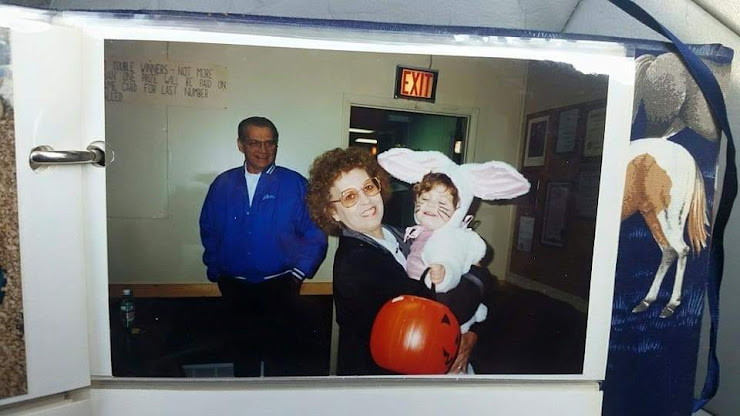

He was well respected, but the softer side of him appeared later in life—after retirement, after the Commandership, after the kids were grown. My mom says they did their best, and they more than made up for it as grandparents. I don’t remember much before he died, but I know this: he’d get down on the floor, let us ride around on his back like a horsey, and laugh. My mom does that now with my girls, which says something about what carries on.

He always wore a blue-and-white jacket (shown above), drove a brown truck, and slicked his hair back with enough gel to stop wind. As a kid, it was weird to touch—until chemo, when he shaved it off and it turned to soft peach fuzz. Years later, I found photos of his natural dark brown hair, before the gel, before the gray, and it blew my mind.

He’d been a bit of a ladies’ man in his youth—the kind of charming trouble you only learn about from old paperwork found in a box decades later. He was complicated. But he stayed, and he provided.

💋 The Coolest Lady Who Ever Lived in Eaton Rapids

That title came from my Uncle Jack, and honestly, he wasn’t wrong.

My Grams—Betty—was the kind of woman who made ordinary life look like theater. She sold Avon at fifteen under her stepmother’s name, became a supervisor at Michigan Bell, and later built her own small empire as a tailor, cake decorator, and neighborhood problem-solver. She was strong, fashionable, and stubborn—sometimes in equal measure.

Their marriage wasn’t perfect, but it was steady. They loved and respected each other, even when it took work. Grandpa knew she kept everyone fed and cared for, and he stood by her through it all. It wasn’t flashy, but it lasted—a kind of commitment this swipe-right generation wouldn’t recognize if it danced up and introduced itself.

When he became State Commander of the American Legion (1995–96) and she became President of the Ladies Auxiliary, it was one of the few times they seemed perfectly in sync. They traveled together, she bought a new outfit for every event—furs in her youth, blazers and pencil skirts later, always with a pin—and they even made it to the White House. Every State Commander was invited, but only a select few were chosen to have breakfast with Hillary Clinton. Grandpa was one of them. Afterwards, they posed for photos with President Bill Clinton and Secretary of Veterans Affairs Jesse Brown—not bad for two small-town Michiganders who started with a dance in a smoky bar.

🎬 The Grams Years

Grams became my second parent. She was at every doctor appointment, every zoo trip, every movie. When we moved to Charlotte, she came out every Saturday to take us shopping, buy a toy (usually at Target), and see a movie at Celebration Cinema.

We’d play Scrabble and Canasta, bake cupcakes, and sit down to her signature beef pot roast or spaghetti—the only spaghetti I’ve ever liked. Dessert was pizzelles, of course. She’s the reason our family started the “find the pickle in the Christmas tree” tradition.

She sewed me a poodle skirt for Kindergarten Round-Up—one of those handmade treasures that made me feel like the star of a 1950s musical. Years later, she drove me and my sisters all the way to Fort Wayne, Indiana, to see a play my friend was in. She crept there at 40 mph and sped home like a getaway driver. Somewhere from that trip, I still have a short video of a guy dancing—and the only recording I have of her voice.

She loved Kelly Clarkson’s Breakaway CD, wore her beret-style hats, and somehow always looked perfectly put together, even if she was just running errands. Her house was never quiet—bird feeders full, hummingbirds zipping around the porch, and later, a parakeet she insisted on feeding spaghetti despite my protests. 🤦♀️

When I started driving, I’d volunteer to take her to her eye appointments—part chauffeur, part excuse to have her to myself. She co-signed my first car, too—a 2006 Volkswagen Beetle affectionately named Ollie Bug.

Eventually, she started calling herself “Gram” after I began calling her “Grams” from watching Charmed. Close enough. 🤦♀️

🐦 Roots, Loss, and the Weird Little Legacies

In the 1970s, Betty raised Saint Bernards—Duke, Duchess, and Lady. Her dogs had championship bloodlines and were registered with the American Kennel Club. She cared for them like family, the kind of devotion that still gets mentioned decades later because, honestly, they were her pride and joy.

They moved often, but their final home had black walnut trees that turned the yard into a harvest each fall. She’d fill a bucket, run the walnuts over with her car to crack the hulls, spread them out on newspaper to dry, then serve them in bowls once shelled. At the edge of the property sat a small pet cemetery for all the family animals. One year, Mom rented ponies for Jessie’s birthday, and Grams hosted them in her yard. Mine kept sneaking off to eat weeds.

She wasn’t always perfect. Toward the end of her life, her mind slipped a bit. She reminisced about her ex-husband, which drove me nuts—he’d abandoned them, while Grandpa stayed and provided. Still, I keep some of her ashes in a blue necklace, our shared September birthstone, because no matter what, she was mine.

🌹 The Last Chapter (for Now)

Grandpa passed in 2002. Grams lived another seventeen years, until 2019. She isn’t beside him yet—he’s buried up north, and she still rests in my mom’s display cabinet with Uncle Jack. We added her death date to the tombstone, but the burial’s on hold; opening the ground runs about $1,200–$1,500, and getting the cemetery folks to answer is half the battle. Someday, though, she’ll rest beside him—finally together, properly.

I’m planning a hummingbird tattoo for her. And starting next year, I’ll hold an annual dinner every November 1—a night to cook each loved one’s favorite meal and tell stories to my daughters.

For Grams: spaghetti and pizzelles.

For Grandpa: venison chili (where do I even buy venison?).

For Uncle Jack: peanut butter cookies.

A weird spread, sure. But so was our family. And that’s what makes it perfect.

She tried so hard to stay alive long enough to meet my first child. But my ex-husband dragged his feet too long, and she missed it. If ghosts were real, I’d believe that would’ve been her unfinished business. Now that I have my babies, I hope she’s finally reunited with Grandpa—the two of them dancing among the stars. 🖤

Leave a Reply